Why behind AI: Modelbusters

What happens when you grow faster than anybody expected?

In the last few weeks we've been covering here the heated discussions around why SaaS is losing momentum and value in the public markets. A lot of that focus has been on the inability of existing incumbents to adapt fast enough to the very rapid pace of change that AI is bringing to the table.

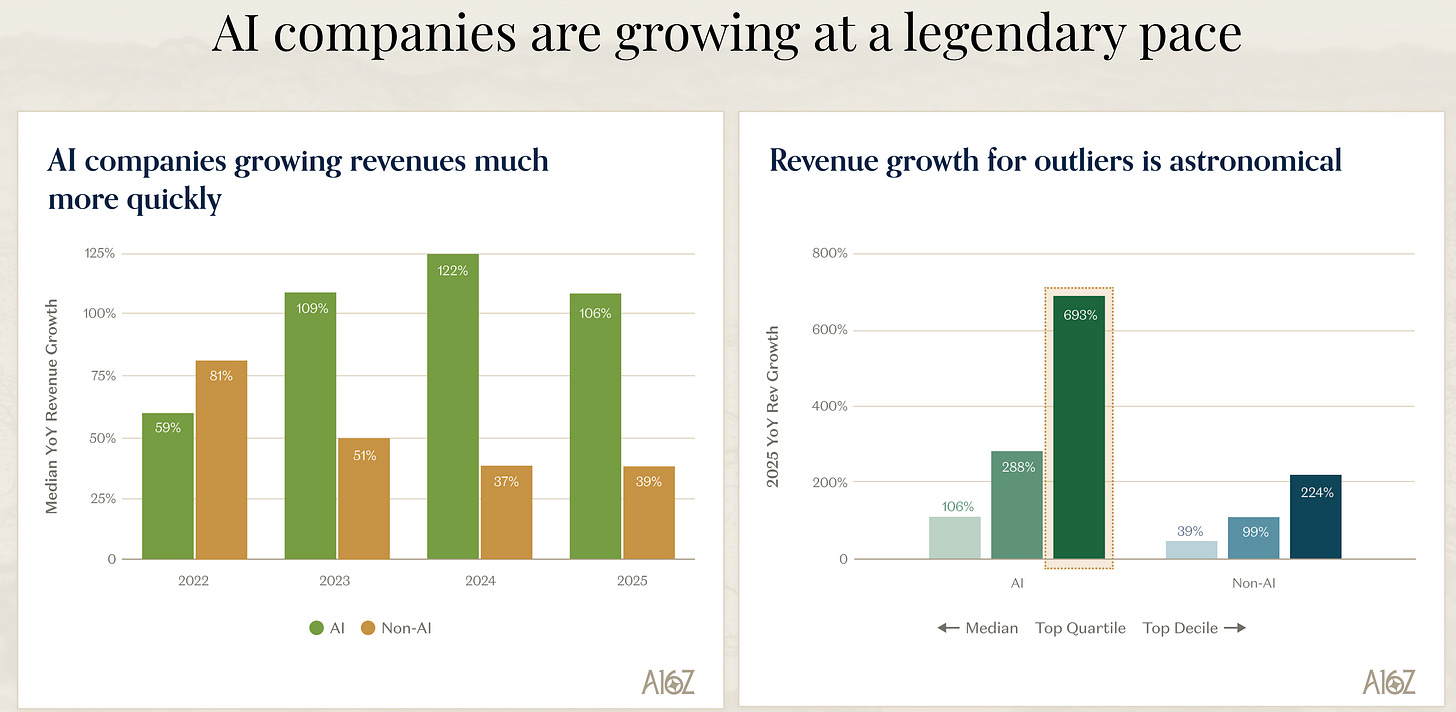

This is not simply a technological change, however. Things have also shifted significantly in how startups actually perform relative to historical data. AI native companies are breaking a number of records and are redefining what the real opportunity in the market is.

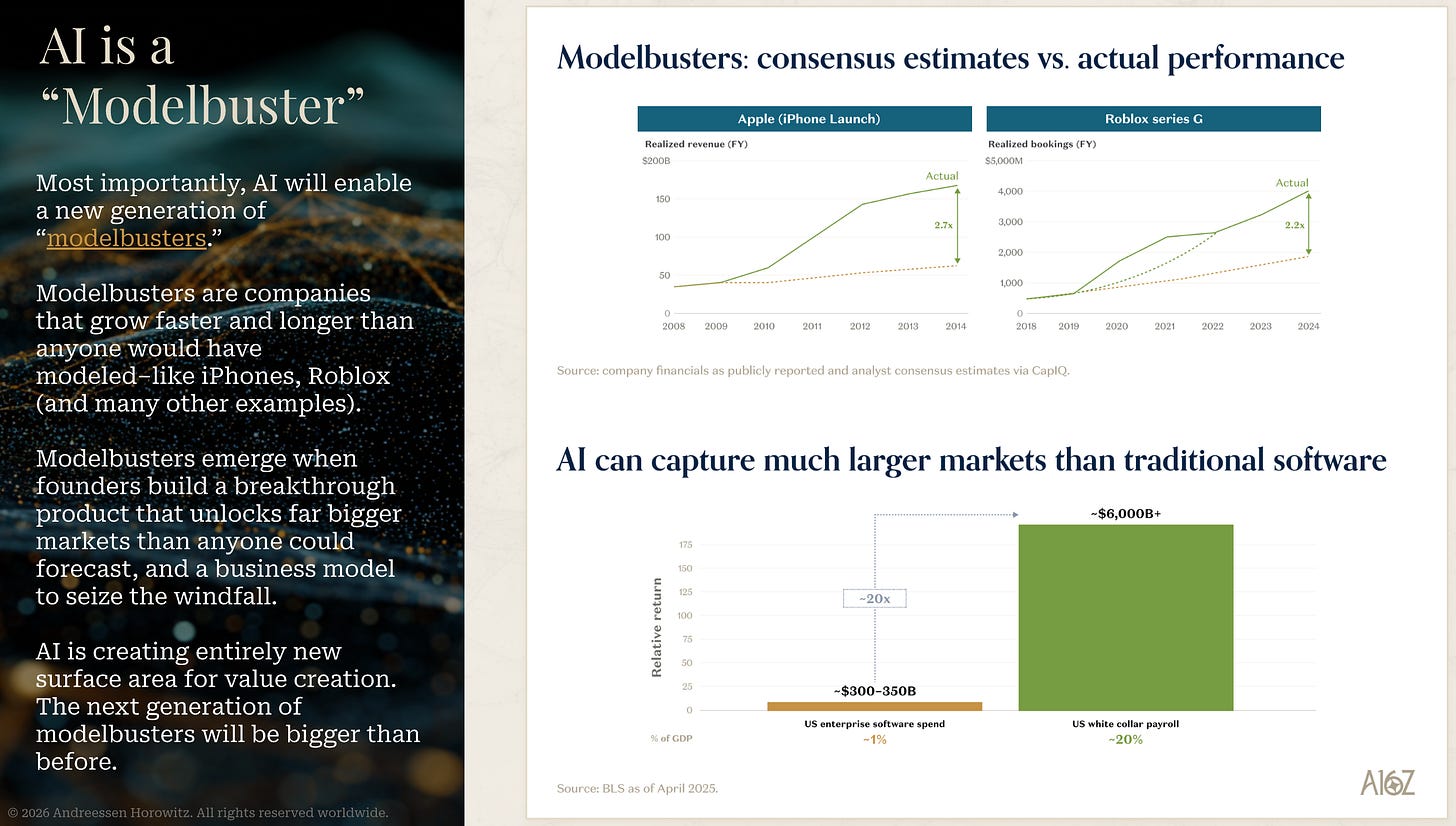

Some call them "modelbusters", implying that none of the existing ways that we evaluate companies are able to handle this shift. Let's review this thesis, through the lens of a16z and their“State of Markets Overview”.

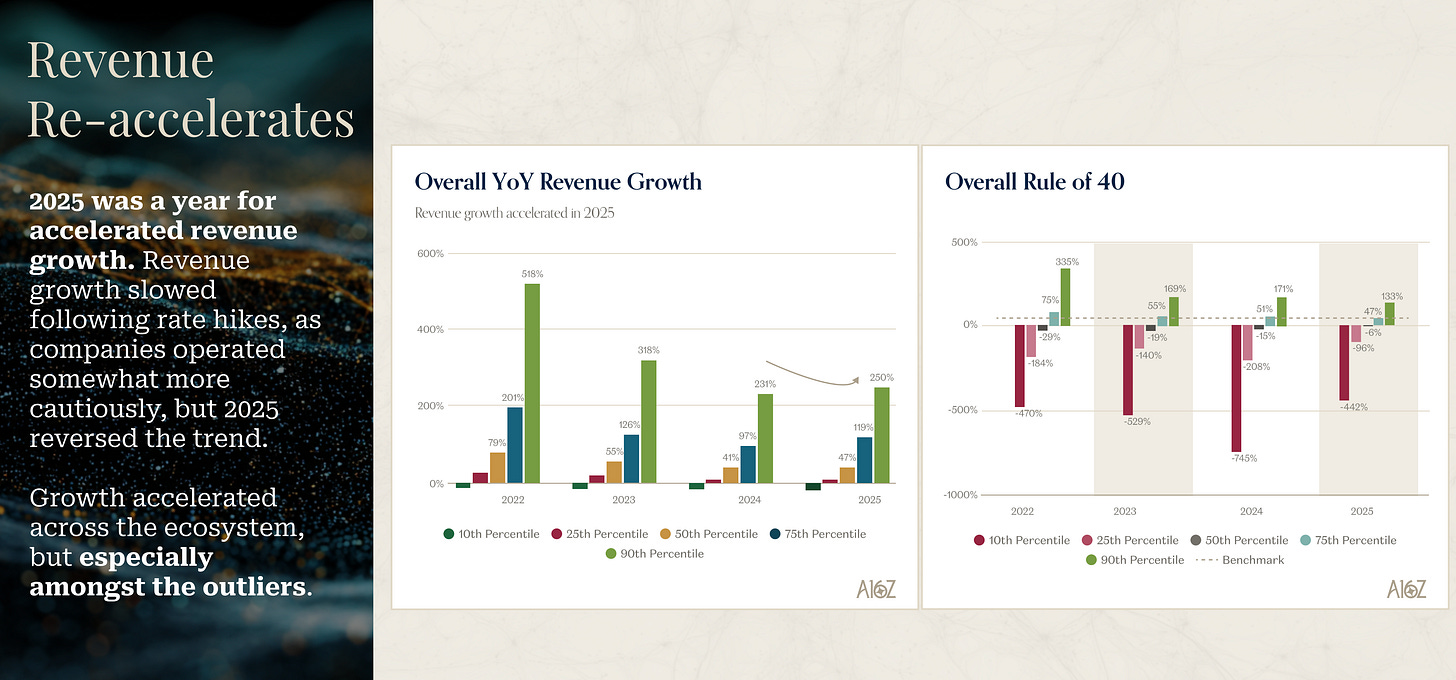

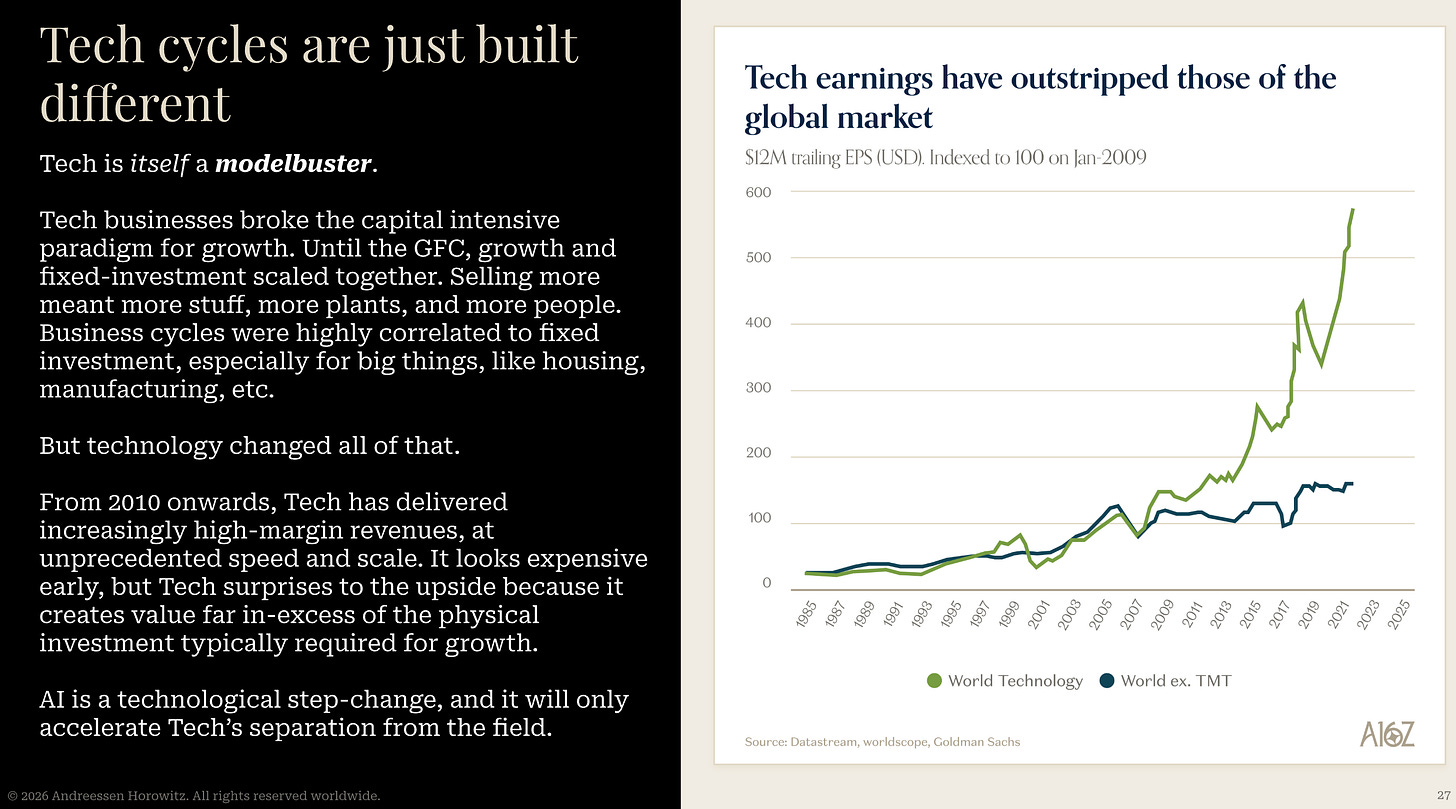

Let's start with the obvious, the spend for technology has accelerated in 2025, lifting "all boats". Both existing tech incumbents and the rapidly growing startups saw an increase in growth on average.

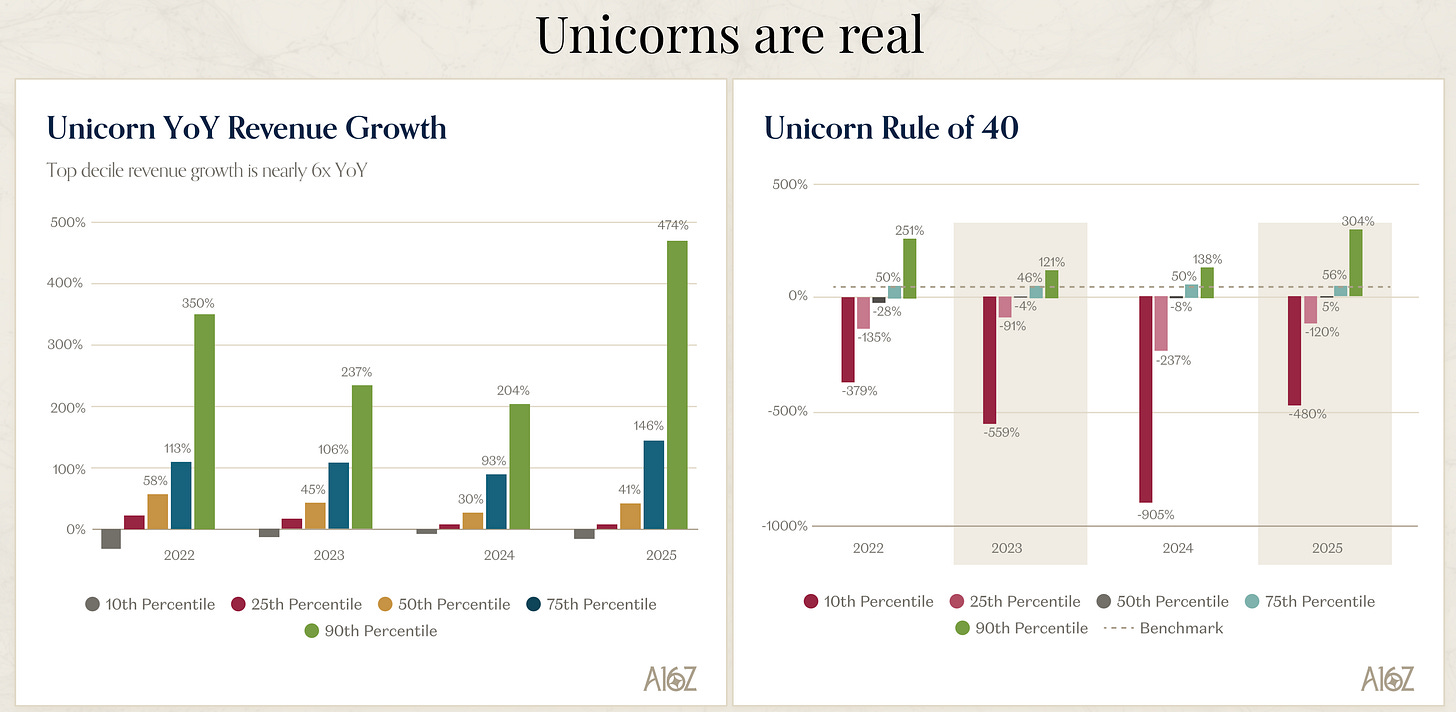

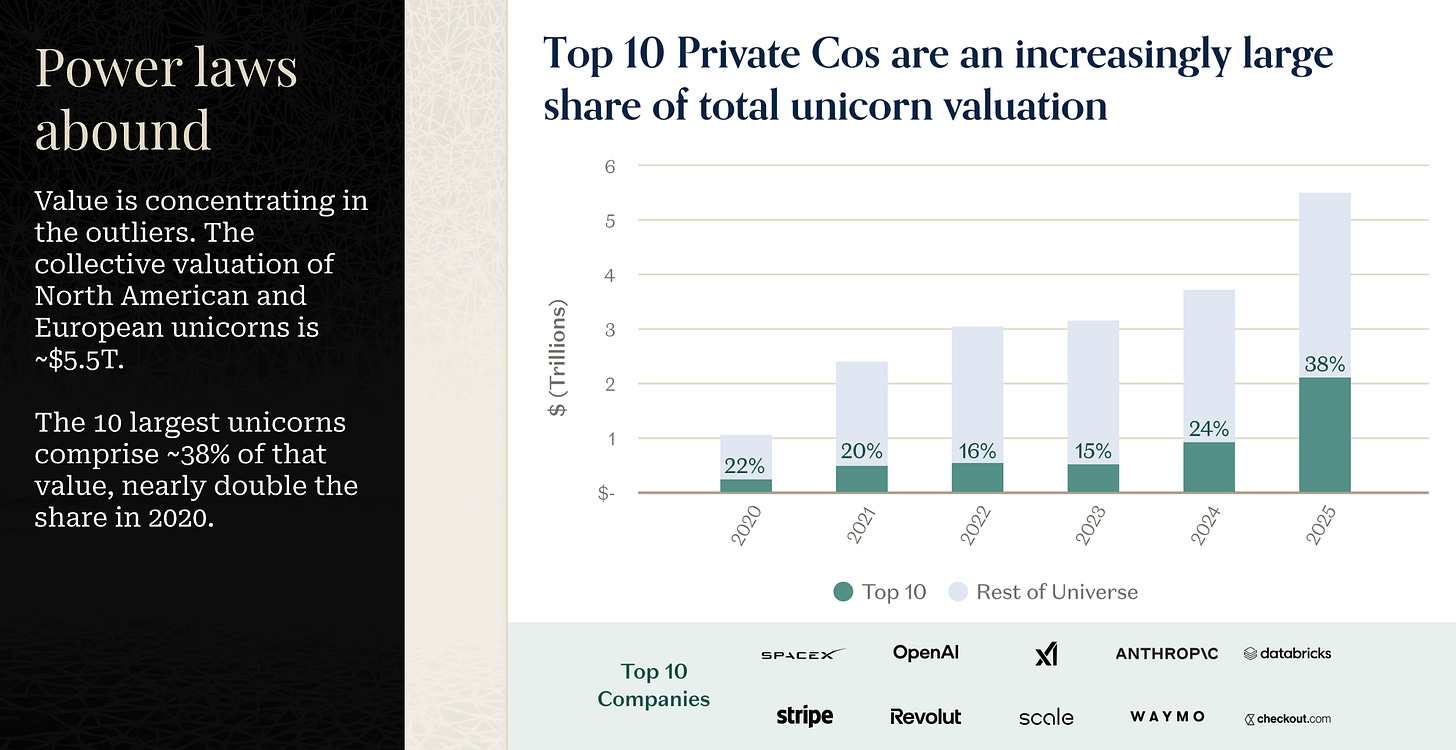

The real story, however, is the outliers, particularly early stage companies. AI-native unicorns are reporting a significant liftoff of usage, which is turning a lot of metrics on its head.

AI companies are not only reporting a much higher growth rate than non-AI startups, but for the big winners in specific categories, they are scaling in an unprecedented way. In my "Best of 2025" post I specifically called out Anthropic for reaching a 900% growth rate from a $1B ARR installed base, which according to technical analysis is considered “absolutely bonkers”.

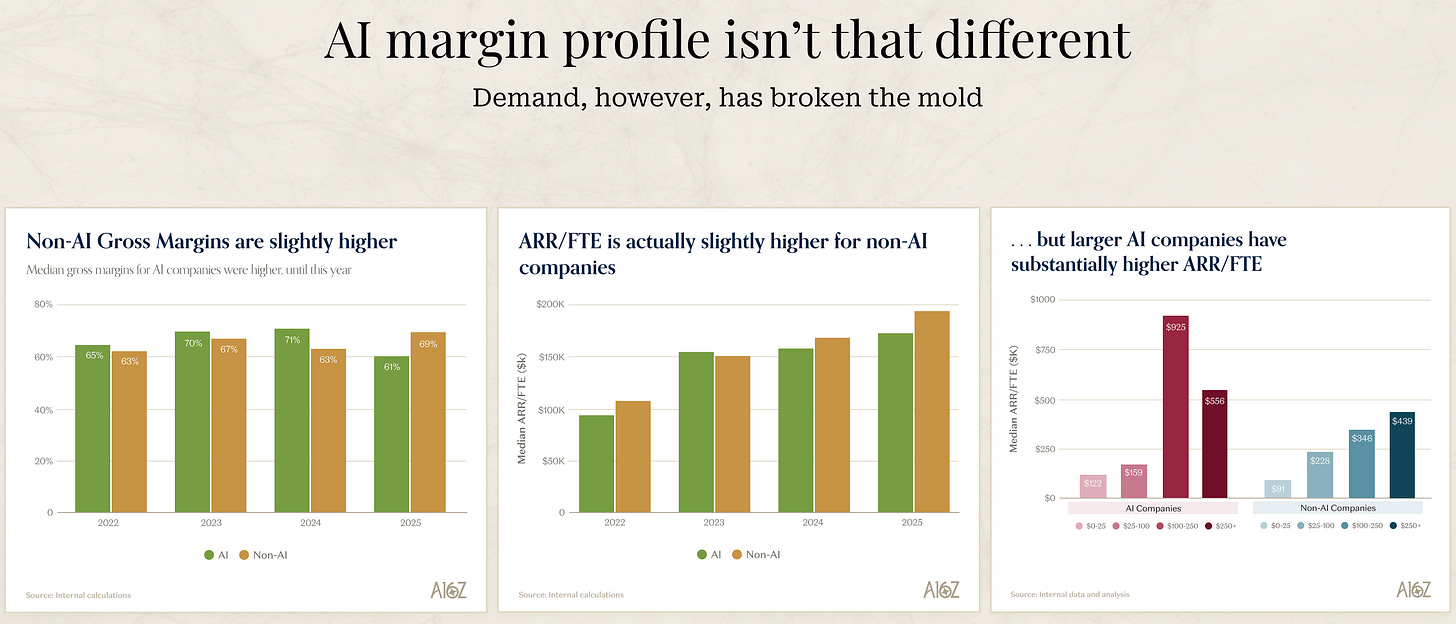

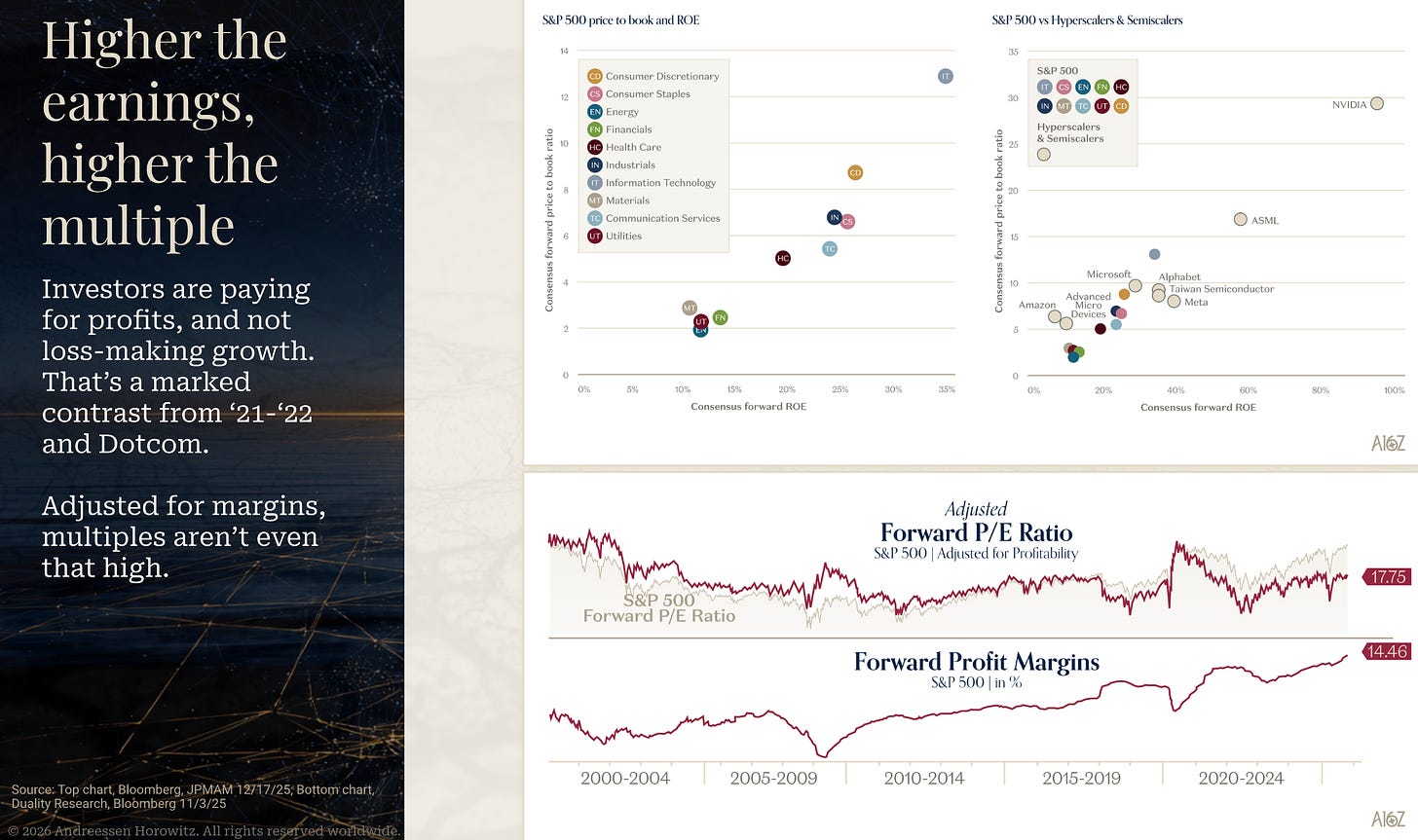

The argument that many had was that "oh, margins are horrible and all of these companies are about to die" which doesn't seem to be the case. More importantly, relative to their scale many of these AI-native companies are significantly more efficient in terms of ARR per employee. This is a significant burden for public SaaS companies, where they essentially have both low productivity per employee and overpay with stock-based compensation which completely removes their profits.

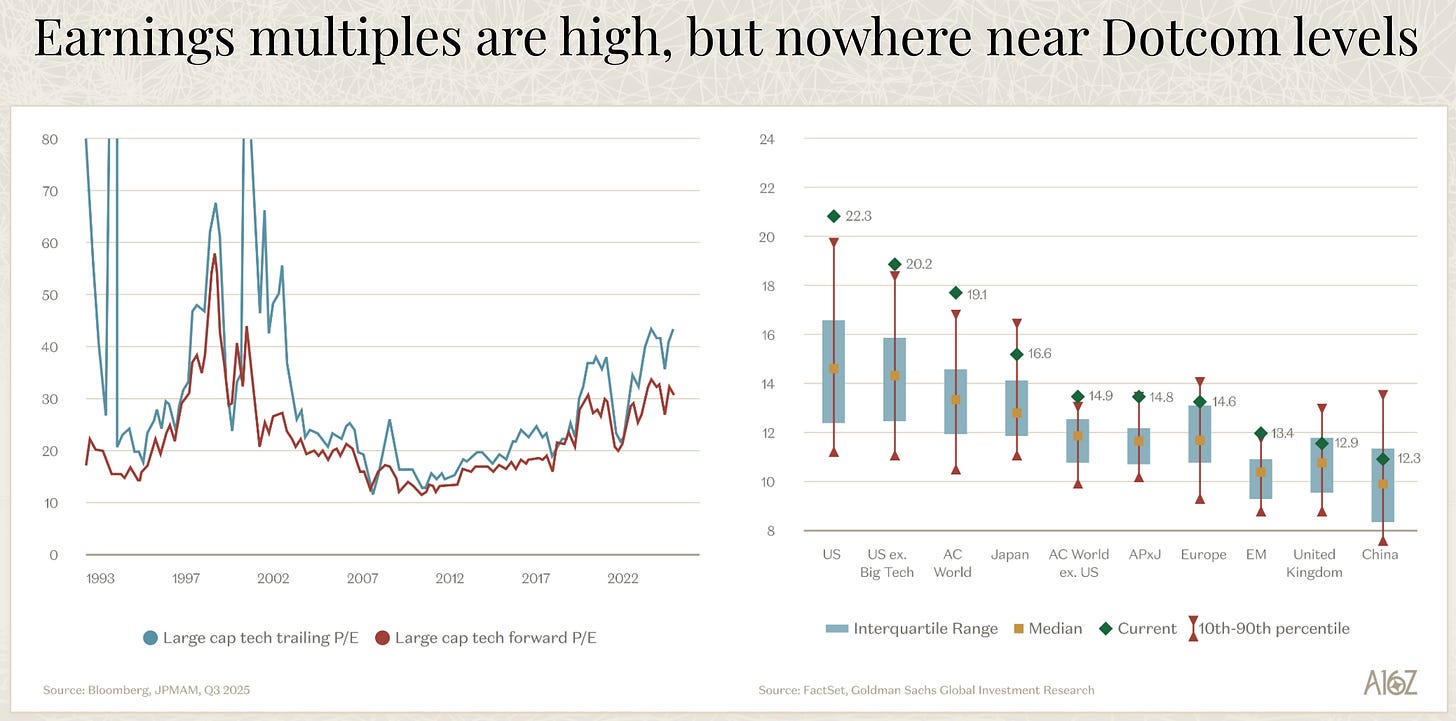

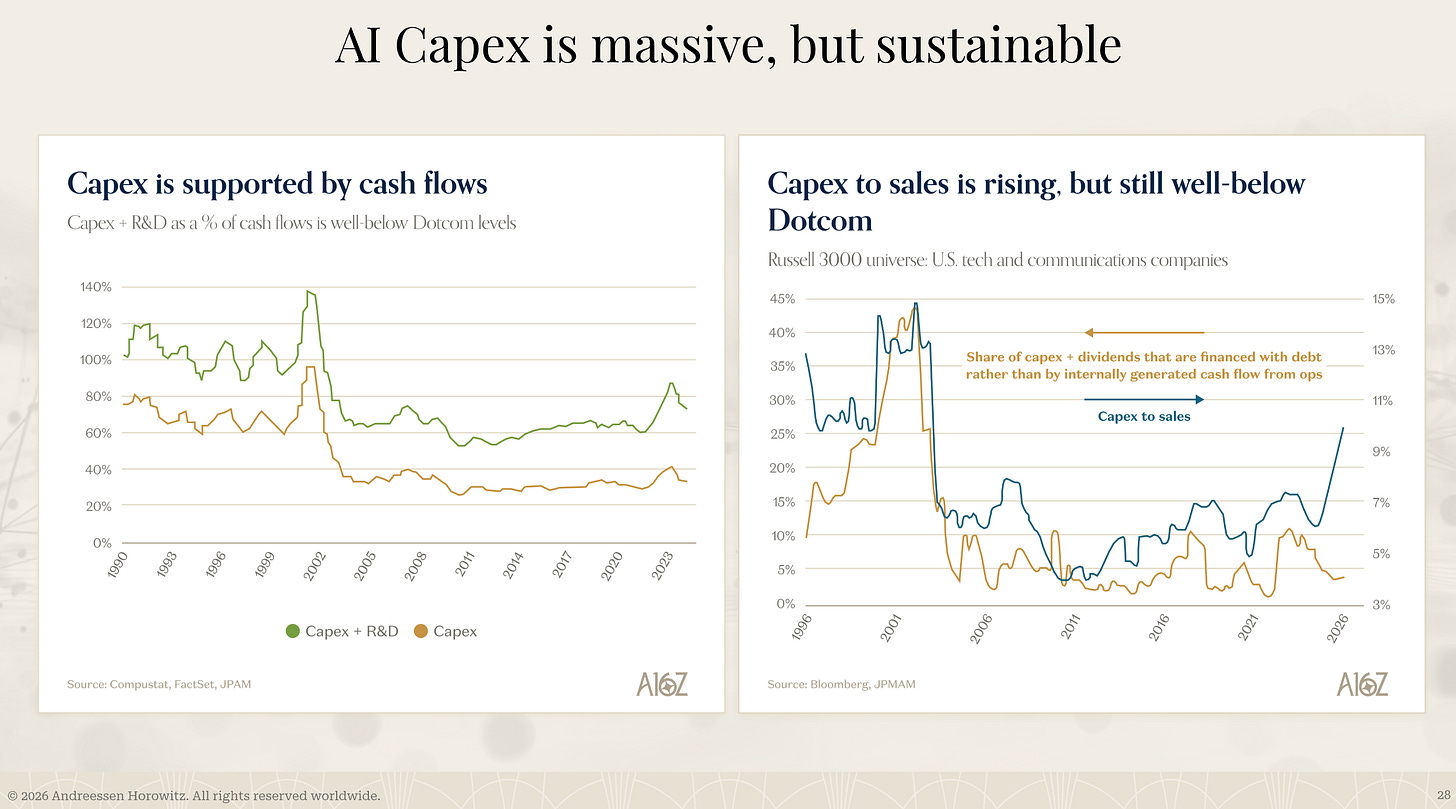

Another big discussion has been "the AI bubble", which some claim is the same thing as any other bubble that ever existed before. The problem with that story is that the main comparison was the Dotcom bubble, which was actually a completely different event, driven by factors that are hardly at play today. While tech companies can definitely be considered "expensive", their valuations are not unreasonable.

The trick, of course, is that currently the best opportunities lie with companies that are operating very high growth businesses but are also sustainable. In public companies today that is rarely in software, but rather in infrastructure. The category of "cloud infrastructure software" is doing amazing, but the value continues to accrue in the bottom of the stack. The inverse relationship is happening in private companies because most early stage hardware companies by definition have very little sustainable growth, while AI-native companies have been capturing a massive demand for the technology.

This new crop of companies can be called modelbusters, because they introduce outliers that are very difficult to account for in the existing way that we project potential growth. If we use existing models, then we are being extremely conservative relative to the results. If we model based on the actual performance, well, then the conclusions are rather dramatic.

To a certain extent, this change is a reflection of tech becoming the dominant force of growth and innovation in the economy.

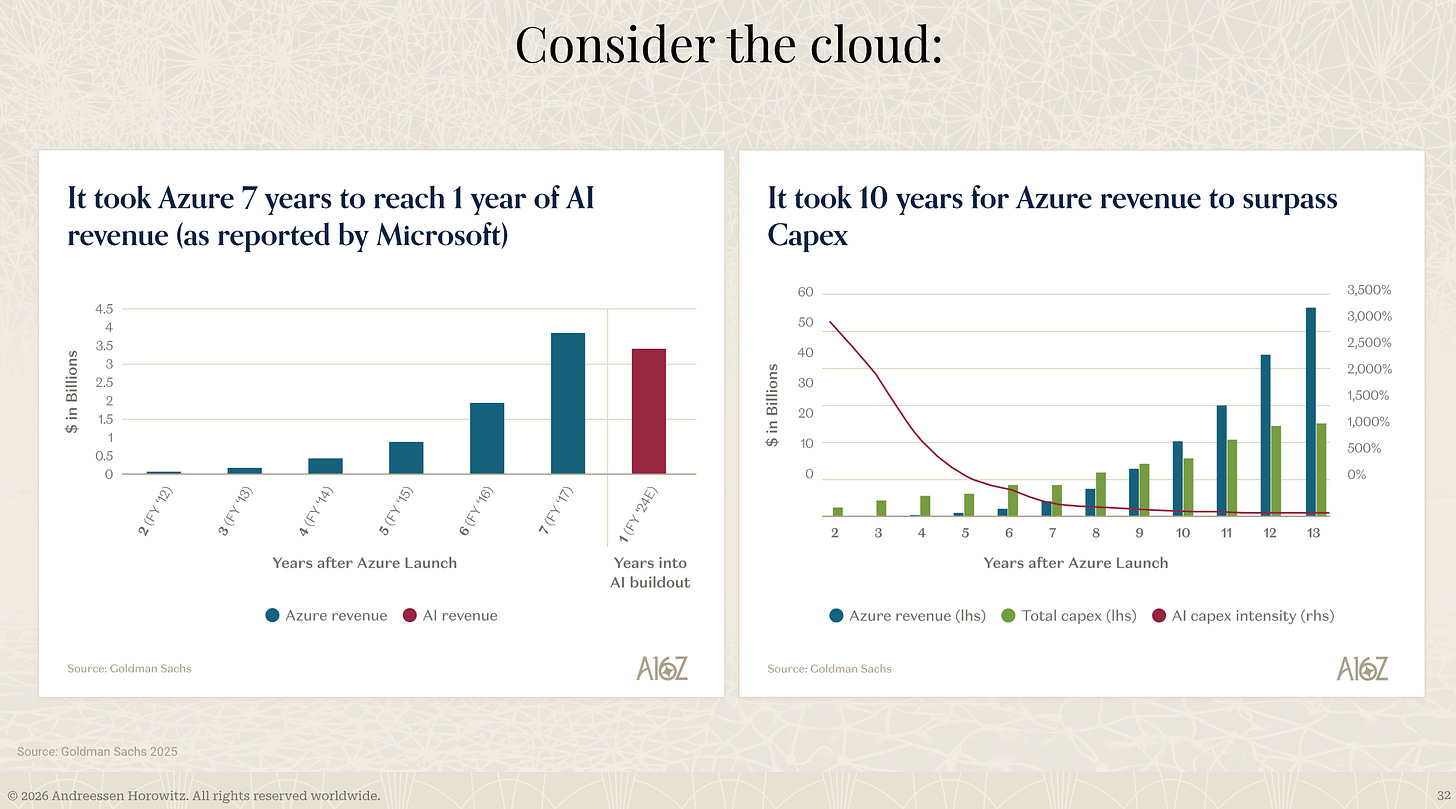

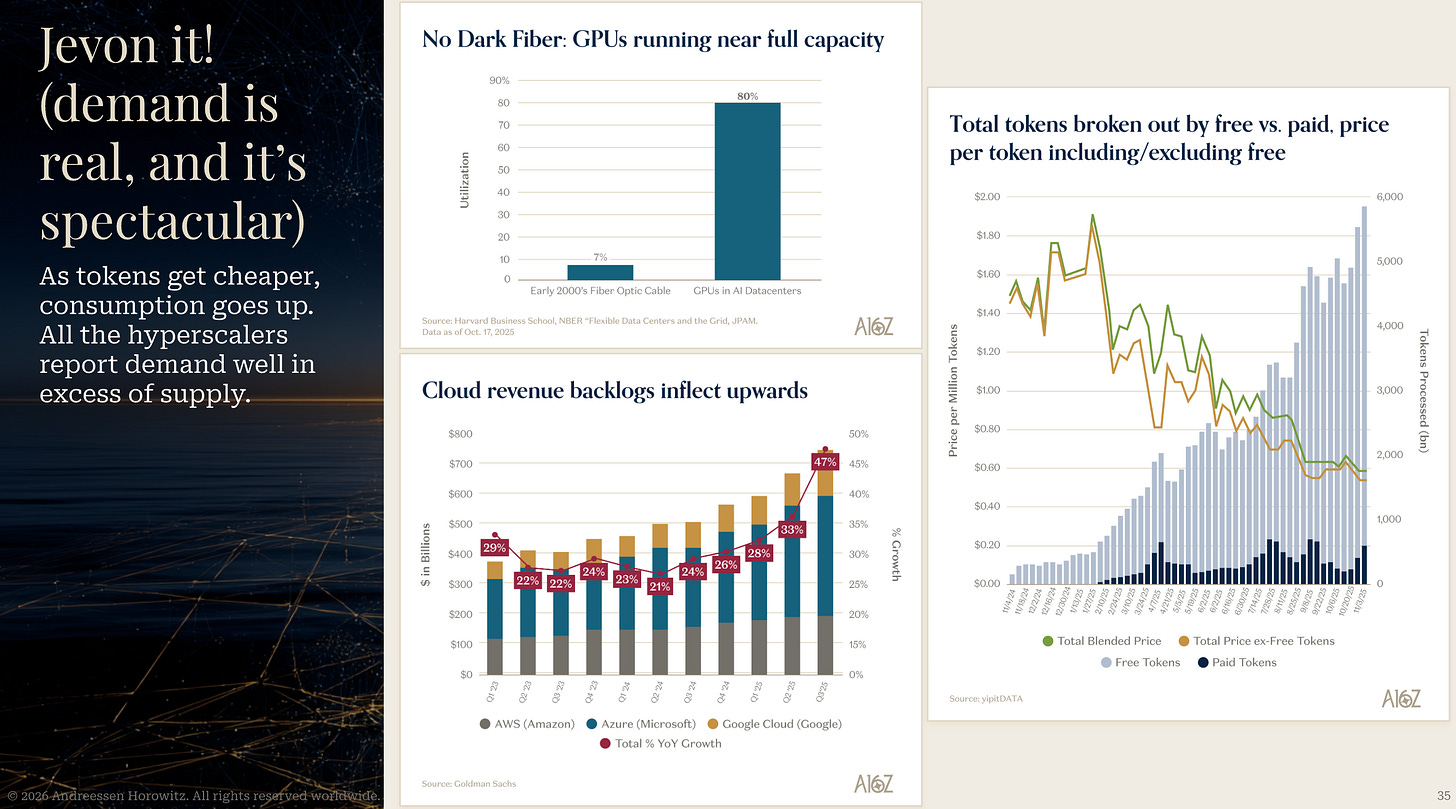

The biggest concern with the "AI bubble" is actually less about whether the startup ecosystem is flooded with too much funding relative to the opportunity, than about the massive infrastructure spend. This is the primary reason why the Dotcom bubble is contrasted repeatedly with the current build out, since at the time a massive investment in the infrastructure that would power the internet was put in place, without the actual users being there. The difference today, of course, is that the users are very much there and their spending is significant.

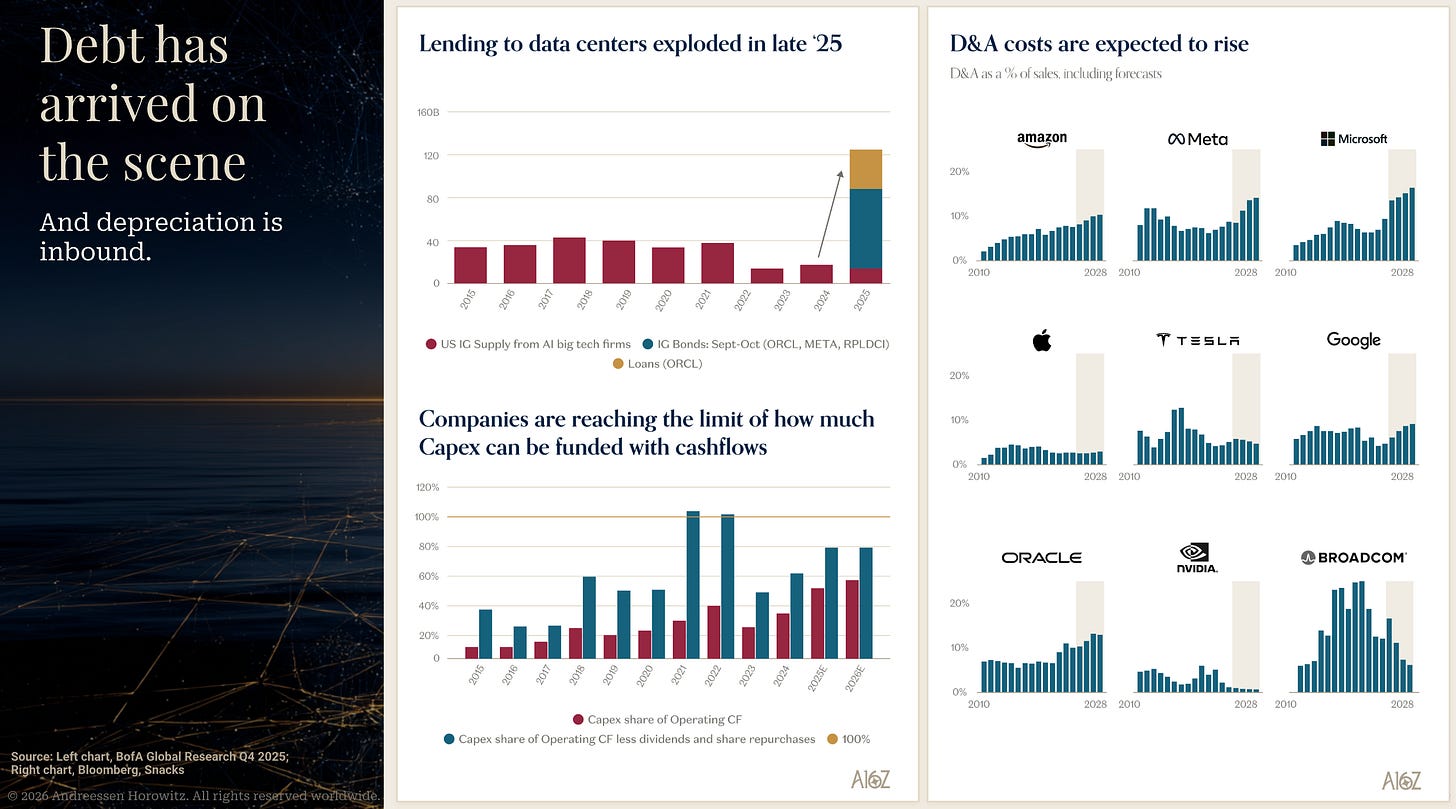

The demand is so high that the existing (and very large) cashflows of the largest tech companies are no longer sufficient to fund the buildout. Companies can opt to delay or even reduce their investments, but then they take asymmetric risks of not being in the right position to capture demand.

"Satya's flinch" literally handicapped the opportunity for Azure to catch up to AWS's revenue and led to an immediate deal with Nebius, who had to jump in with their available compute in order to solve infrastructure gaps.

The “cautiousness” of seasoned leaders at the hyperscalers makes sense, since this type of growth is something that they’ve never had before, even if the move to cloud was itself a dramatic shift in growth for tech companies.

Jevons paradox is an economics idea that says making the use of a resource more efficient can end up increasing total use of that resource instead of reducing it. This has been a consistent theme throughout the last year, as optimizations and price cuts have mostly made it possible to fit a lot more tokens in the ever expanding budgets.

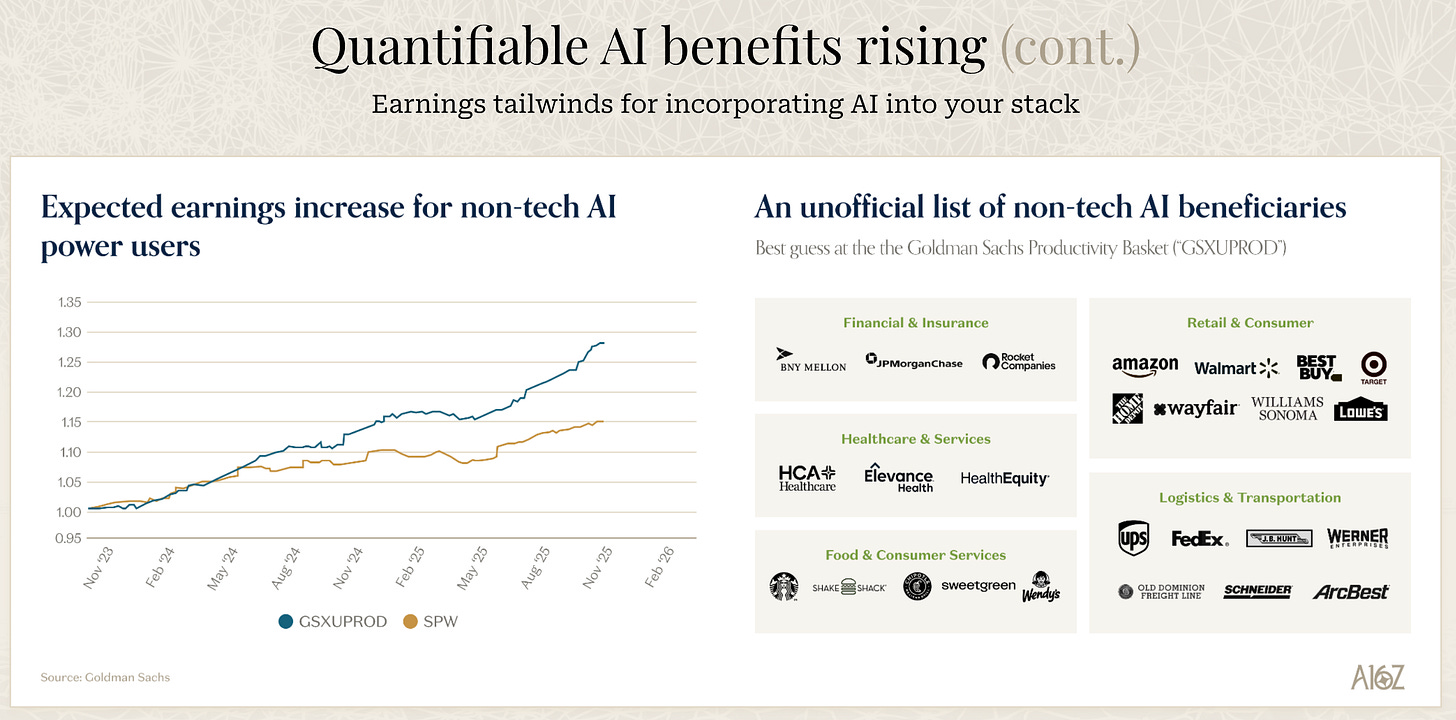

The ongoing meme caused by the “95% of all AI pilots go nowhere” study is that AI is useless for most companies. This doesn’t seem to reflect what many of those leaders are saying (and it can’t be that all of them are shilling for AI in order to look smarter). As I covered back in August:

The “95% failure rate” sound bite basically refers only to what they ranked as niche implementations for specific business processes, and those were mostly driven by attempts at homegrown solutions. So we are playing a bit of a wordcel game here, pretending that the massive and quick adoption of LLMs is less relevant than “copilot for vending machines” failing a poorly run pilot.

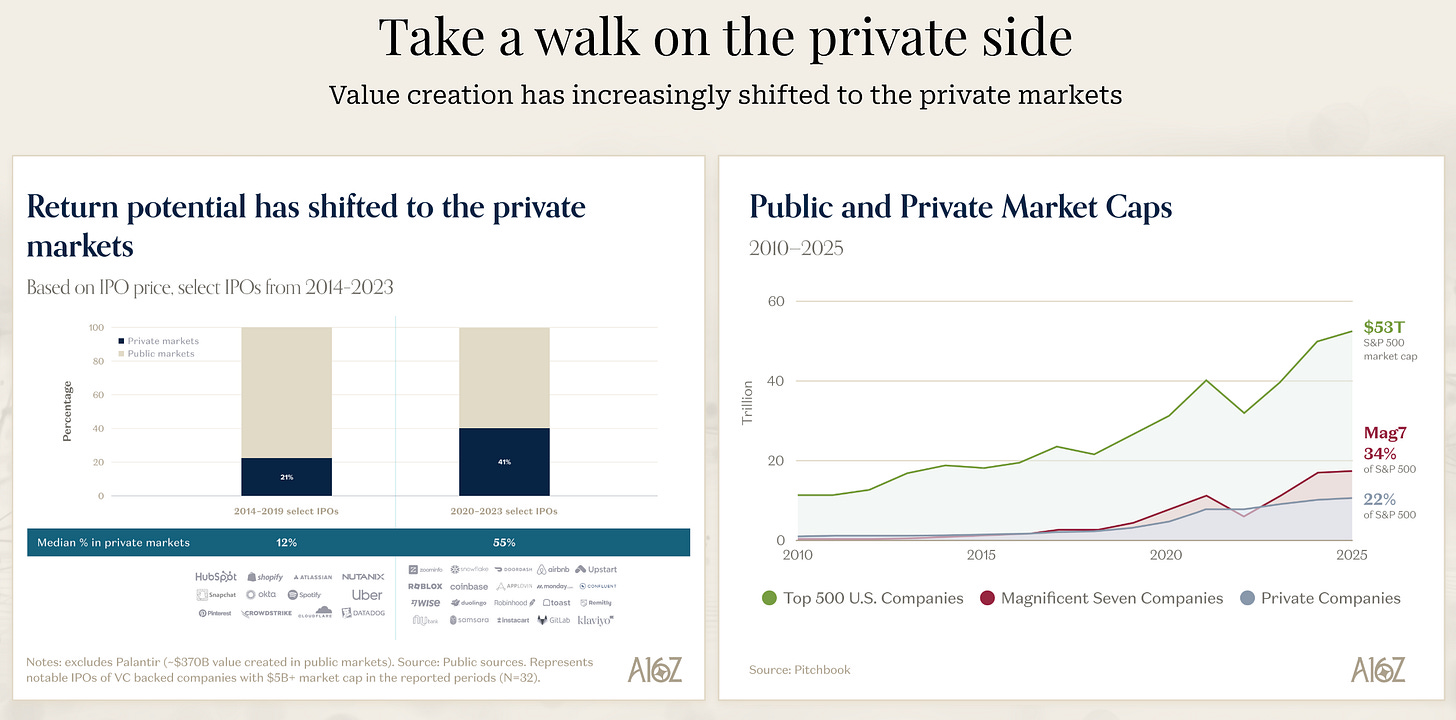

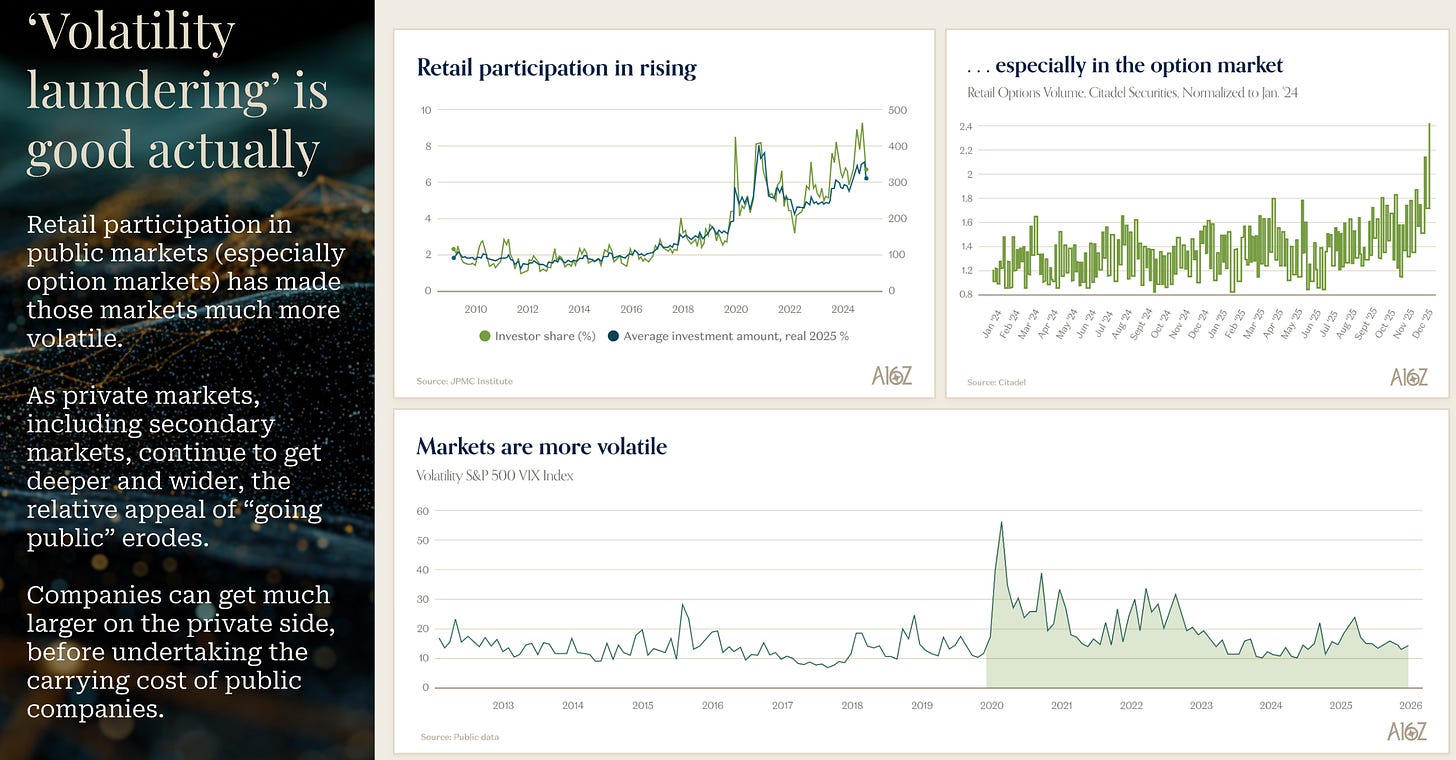

Part of the frustration for public investors is that outside of the infrastructure layer, SaaS has underperformed as value has accrued predominantly to private companies.

The speculation this year is that we will finally see some of the private market whales go public. It's still a bit questionable what the point of doing that is, as we've seen Databricks maneuver themselves into the leading position for data+AI without having the scrutiny (and often loss of focus) of having to deal with the quarterly earnings drama. SpaceX is an exception due to the strong bid that will come from both retail and professional investors. At the end of the day, it's a literal monopoly with strong fundamentals, what's not to like?

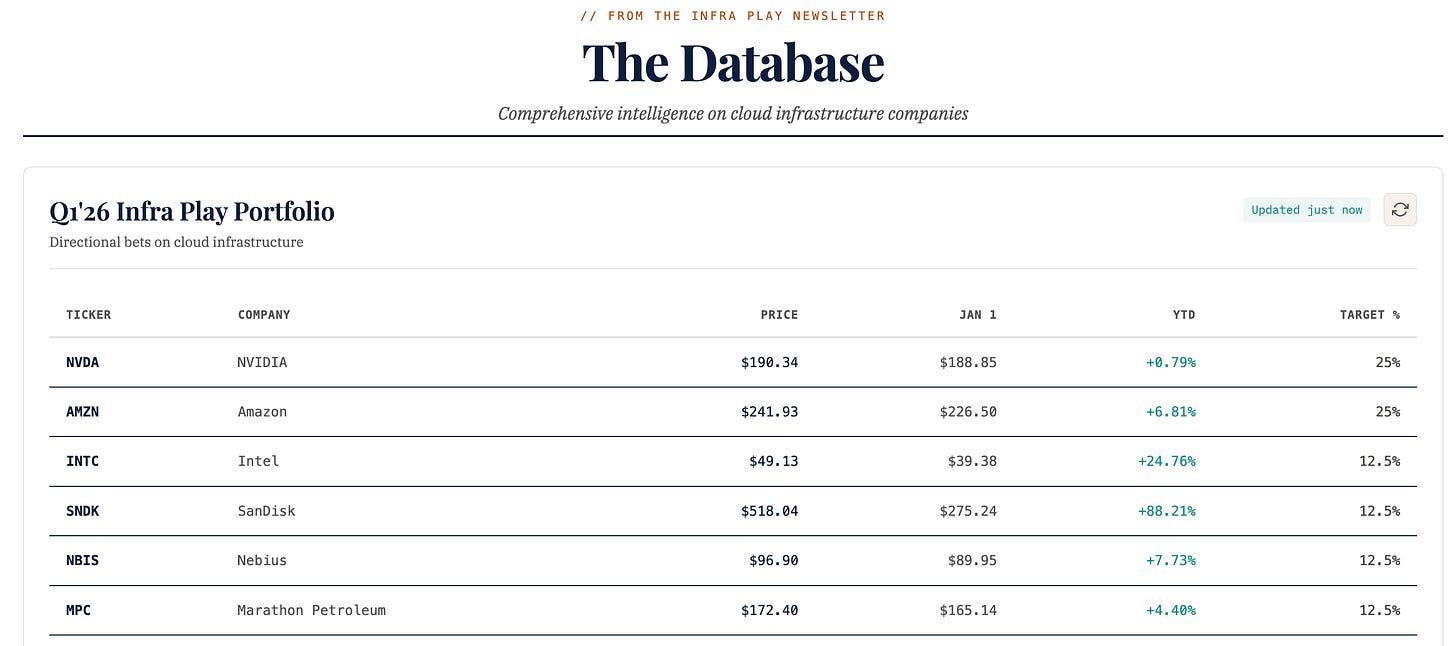

Cloud infrastructure software is becoming a hotbed for retail gambling, as many are starting to use leverage in order to make directional bets. Whether that's a positive or a negative is a different topic, but it's not difficult to see why many leaders of high growth AI-native companies see very little reason to waste their time and effort defending "the stock price", while both retail and the professionals are trying to ride sentiment. Speaking of more strategic bets, let's close this market update with how our Infra Play portfolio is doing.

Not too shabby! Maybe there is something to the thesis.